Cerveau

Un article de Vev.

(Différences entre les versions)

| Version du 3 mai 2012 à 18:44 Vev (Discuter | contribs) (→liens) ← Différence précédente |

Version du 3 mai 2012 à 18:47 Vev (Discuter | contribs) Différence suivante → |

||

| Ligne 1: | Ligne 1: | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| == sujet == | == sujet == | ||

| Ligne 36: | Ligne 34: | ||

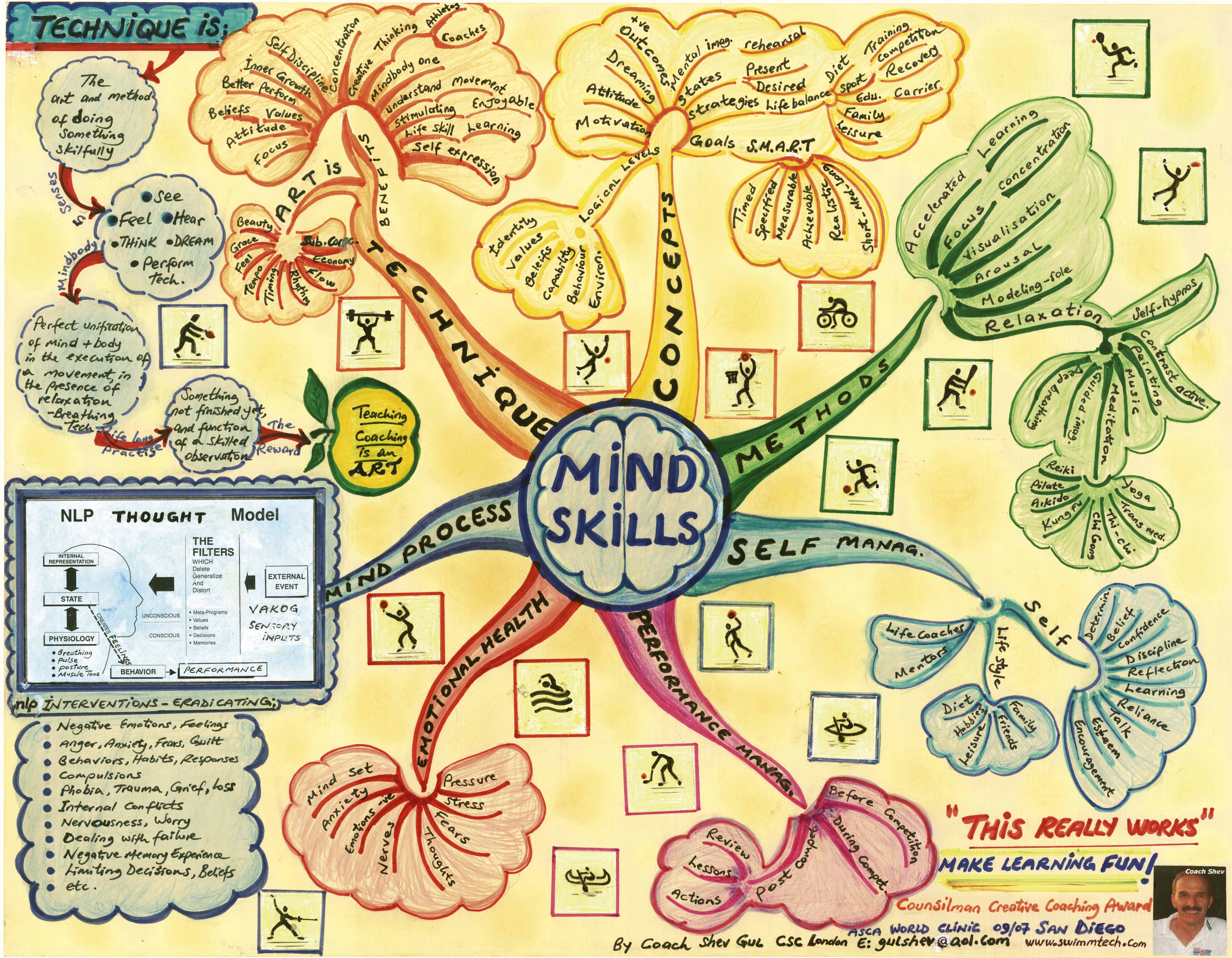

| http://publishingacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/brain-mindmap.jpg | http://publishingacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/brain-mindmap.jpg | ||

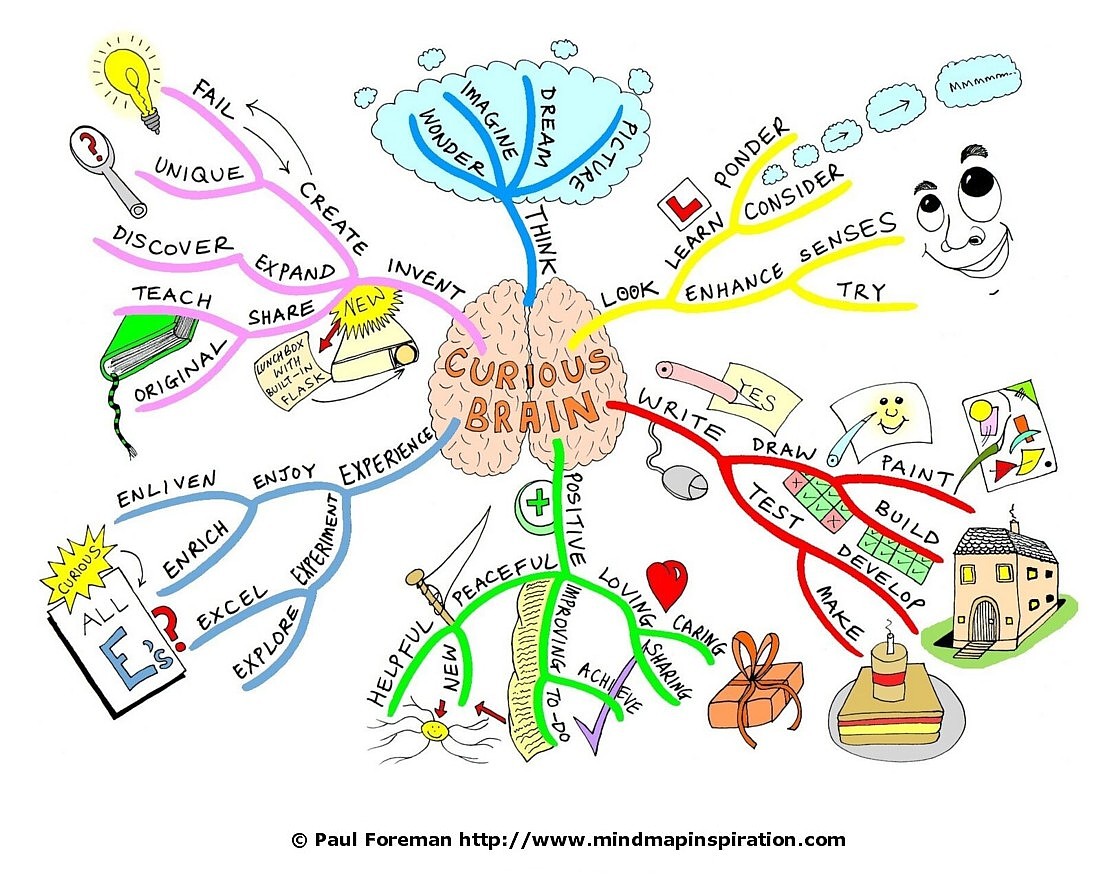

| http://www.mindmapinspiration.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/curious-brain-mind-map-10.jpg | http://www.mindmapinspiration.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/curious-brain-mind-map-10.jpg | ||

| - | |||

| - | == wikipedia == | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | [[Image:Chimp Brain in a jar.jpg|thumb|Cerveau d'un [[chimpanzé]].]] | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le '''cerveau''' est le principal [[organe]] du [[système nerveux]] des [[animal|animaux]]. Au sens strict, le cerveau est l'ensemble des structures nerveuses dérivant du [[prosencéphale]] ([[diencéphale]] et [[télencéphale]]). Dans le [[langage courant]], ce terme peut désigner soit l'[[encéphale]] dans son ensemble, soit le seul [[télencéphale]] ou même le seul [[cortex cérébral]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chez les [[vertébrés]], le cerveau est situé dans la [[tête (anatomie)|tête]], protégé par le [[crâne]], et son volume varie grandement d'une [[espèce (biologie)|espèce]] à l'autre. Par [[analogie]], chez les [[invertébré]]s, le cerveau désigne certains centres nerveux. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau régule les autres [[Système d'organes|systèmes d'organes]] du corps, en agissant sur les [[muscle]]s ou les [[glande]]s, et constitue le siège des fonctions [[cognition|cognitives]]. Ce contrôle centralisé de l'organisme permet des réponses rapides et coordonnées aux variations environnementales. Les [[réflexe (réaction motrice)|réflexes]], schémas de réponses simples, ne nécessitent pas l'intervention du cerveau. Toutefois, les comportements plus sophistiqués nécessitent que le cerveau intègre les informations transmises par les [[Système sensoriel|systèmes sensoriels]] et fournissent une réponse adaptée. | ||

| - | |||

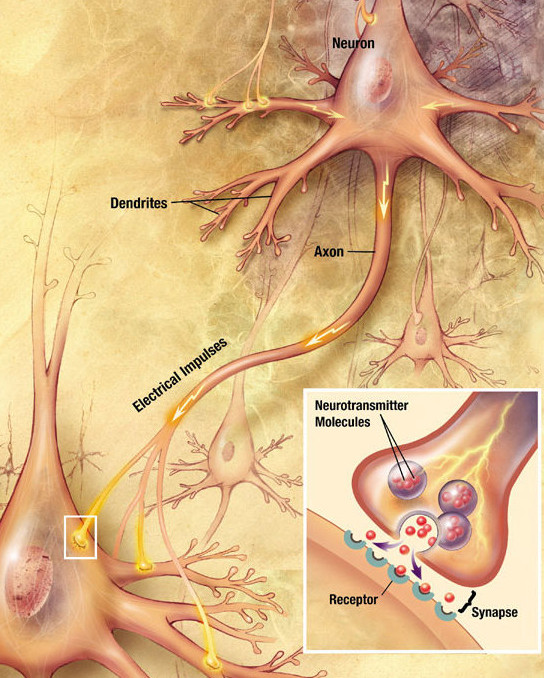

| - | Le cerveau est une structure extrêmement complexe qui peut renfermer jusqu'à plusieurs milliards de [[neurone]]s connectés les uns aux autres. Les neurones sont les [[Cellule (biologie)|cellules]] cérébrales qui communiquent entre elles par le biais de longues fibres protoplasmiques appelées [[axone]]s. L'axone d'un neurone transmet des [[influx nerveux]], les [[Potentiel d'action|potentiels d'action]], à des cellules cibles spécifiques situées dans des régions plus ou moins distantes du cerveau ou de l'organisme. Les [[cellule gliale|cellules gliales]] sont le deuxième type cellulaire du cerveau et assurent des fonctions très diversifiées, centrées autour du support des neurones et de leurs fonctions. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Malgré de grandes avancées en [[neurosciences]], le fonctionnement du cerveau est encore mal connu. Les relations qu'il entretient avec l'[[esprit]] sont le sujet de nombreuses discussions, aussi bien [[philosophique]]s que [[scientifique]]s. | ||

| - | |||

| - | == Anatomie == | ||

| - | [[Fichier:Bilaterian-plan.svg|thumb|Schéma d'organisation fondamental d'un bilatérien.]] | ||

| - | Le cerveau est la structure biologique la plus complexe connue<ref name=shepherd>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=G. M.|nom1=Shepherd|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Neurobiology|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=3|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Oxford University Press|éditeur=Oxford University Press|lieu=|année=1994|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=760|format=|isbn=9780195088434|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=3|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/?id=zr4WRMw0xRQC|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref> ce qui rend souvent délicate la comparaison de cerveaux de différentes espèces à partir de leur apparence. Néanmoins, l'architecture du cerveau présente plusieurs caractéristiques communes à un grand nombre d'espèces. Trois approches complémentaires permettent de les mettre en évidence. L'approche [[Évolution (biologie)|évolutionniste]] compare l'anatomie du cerveau entre différentes espèces et repose sur le principe que les [[Caractère (biologie)|caractères]] retrouvés sur toutes les branches descendantes d'un ancêtre donné étaient aussi présentes chez leur [[ancêtre commun]]. L'approche [[Neurodéveloppement|développementale]] étudie le processus de formation du cerveau du stade [[embryon]]naire au stade [[adulte]]. Enfin, l'approche [[génétique]] analyse l'[[Expression génétique|expression]] des [[gène]]s dans les différentes zones du cerveau. | ||

| - | |||

| - | L'origine du cerveau remonte à l'apparition des [[Bilateria|bilatériens]], une des principales subdivisions du [[règne animal]] notamment caractérisée par une [[symétrie bilatérale]] des organismes, il y a environ 550-560 [[Million d'années|millions d'années]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=G.|nom1=Balavoine|lien auteur1=|prénom2=A.|nom2=Adoutte|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=The Segmented Urbilateria: A Testable Scenario|sous-titre=|périodique=Integr. Comp. Biol.|lien périodique=Integrative and Comparative Biology|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=43|titre volume=|numéro=1|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=|année=2003|pages=137-147|issn=1540-7063|issn2=1557-7023|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/1/137.full.pdf+html|doi=10.1093/icb/43.1.137| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. L'ancêtre commun de ce taxon suivait un [[plan d'organisation]] de type [[Tube|tubulaire]], [[ver]]miforme et [[Métamérisation|métamérisé]] ; un schéma qui continue de se retrouver dans le corps de tous les bilatériens actuels, dont l'[[Homme]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=A.|nom1=Schmidt-Rhaesa|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=The evolution of organ systems|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Oxford University Press|éditeur=Oxford University Press|lieu=|année=2007|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=385|format=|isbn=9780198566694|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=110|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=ZACR7ZO_65YC&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Ce plan d'organisation fondamental du corps est un [[tube]] renfermant un [[tube digestif]], reliant la [[bouche]] et l'[[anus]], et un [[cordon nerveux]] qui porte un [[Ganglion nerveux|ganglion]] au niveau de chaque métamère du corps et notamment un ganglion plus important au niveau du front appelé « cerveau ». | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Invertébrés === | ||

| - | |||

| - | La composition du cerveau des [[invertébrés]] est très différente de celle des [[vertébrés]], à tel point qu'il est difficile de comparer les deux structures à moins de se baser sur la [[génétique]]. Deux groupes d'invertébrés se démarquent par un cerveau relativement complexe : les [[arthropodes]] et les [[céphalopodes]]<ref name="butler">{{article|langue=en|prénom1=A. B.|nom1=Butler|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Chordate evolution and the origin of craniates: An old brain in a new head|sous-titre=|périodique=Anat. Rec.|lien périodique=Anatomical Record|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=261|titre volume=|numéro=3|titre numéro=|jour=15|mois=juin|année=2000|pages=111-125|issn=1932-8494|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1002/1097-0185(20000615)261:3<111::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-F| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Le cerveau de ces deux groupes provient de deux cordons nerveux parallèles qui s'étendent à travers tout le corps de l'animal. Les arthropodes ont un cerveau central avec trois divisions et de larges lobes optiques derrière chaque [[œil]] pour le [[Vue|traitement visuel]]<ref name="butler"/>. Les céphalopodes possèdent le plus gros cerveau de tous les invertébrés. Le cerveau des pieuvres est très développé, avec une complexité similaire à celle rencontrée chez les vertébrés. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau de quelques invertébrés a été particulièrement étudié. Par la simplicité et l'accessibilité de son système nerveux, l'[[aplysie]] a été choisie comme modèle par le [[Neurophysiologie|neurophysiologiste]] [[Eric Kandel]] pour l'étude des bases moléculaires de la mémoire qui lui valut un [[Prix Nobel de physiologie ou médecine|Prix Nobel]] en [[2000]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=E. R.|nom1=Kandel|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=In search of memory: the emergence of a new science of mind|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=W. W. Norton & Co.|lieu=|année=2007|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=510|format=|isbn=9780393329377|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=LURy5gojaDoC&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Cependant, les cerveaux d'invertébrés les plus étudiés demeurent ceux de la [[drosophile]] et du [[Nematoda|ver nématode]] ''[[Caenorhabditis elegans]]''. Du fait de l'important panel de techniques à disposition pour étudier leur [[matériel génétique]], les drosophiles sont tout naturellement devenues un sujet d'étude sur le rôle des [[gène]]s dans le développement du cerveau<ref>{{Lien web|url=http://flybrain.neurobio.arizona.edu/ |titre=Flybrain: An online atlas and database of the ''drosophila'' nervous system|id= |série= |auteur= |lien auteur= |coauteurs= |date= |année= |mois= |site= |éditeur=Département d'entomologie de l'université du Colorado |isbn= |page= |citation= |en ligne le= |consulté le=29 octobre 2010 }}</ref>. De nombreux aspects de la neurogénétique des drosophiles se sont avéré être également valable chez l'Homme. Par exemple, les premiers gènes impliqués dans l'[[horloge circadienne|horloge biologique]] furent identifiés dans les [[années 1970]] en étudiant des drosophiles mutantes montrant des perturbations dans leur cycles journaliers d'activité<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=R. J.|nom1=Konopka|lien auteur1=|prénom2=S.|nom2=Benzer|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Clock Mutants of ''Drosophila melanogaster''|sous-titre=|périodique=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA|lien périodique=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=68|titre volume=|numéro=9|titre numéro=|jour=1|mois=septembre|année=1971|pages=2112-2116|issn=0027-8424|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://www.pnas.org/content/68/9/2112.full.pdf+html|doi=| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Une recherche sur le [[génome]] des vertébrés a montré un ensemble de [[Analogie (évolution)|gènes analogues]] à ceux de la drosophile jouant un rôle similaire dans l'horloge biologique de la souris et probablement également dans celle de l'Homme<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=H.-S.|nom1=Shin|lien auteur1=|prénom2=T. A.|nom2=Bargiello|lien auteur2=|prénom3=B. T.|nom3=Clark|lien auteur3=|prénom4=F. R.|nom4=Jackson|lien auteur4=|prénom5=M. W.|nom5=Young|lien auteur5=|traduction=|titre=An unusual coding sequence from a ''Drosophila'' clock gene is conserved in vertebrates|sous-titre=|périodique=Nature|lien périodique=Nature (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=317|titre volume=|numéro=6036|titre numéro=|jour=3|mois=octobre|année=1985|pages= 445-448|issn=0028-0836|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1038/317445a0| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | Comme la drosophile, le nématode ''C. elegans'' a été très étudié en génétique<ref>{{Lien web|url= http://www.wormbook.org/|titre=WormBook: The online review of ''C. Elegans'' biology |id= |série= |auteur= |lien auteur= |coauteurs= |date= |année= |mois= |site= |éditeur= |isbn= |page= |citation= |en ligne le= |consulté le= 30 octobre 2010}}</ref> car son plan d'organisation est très stéréotypé : le système nerveux du morphe [[Hermaphrodisme|hermaphrodite]] possède exactement 302 [[neurone]]s, toujours à la même place, établissant les mêmes [[Synapse|liaisons synaptiques]] pour chaque ver<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=O.|nom1=Hobert|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Specification of the nervous system|sous-titre=|périodique=WormBook|lien périodique=WormBook|éditeur=The C. elegans Research Community|lieu=|série=|volume=|titre volume=|numéro=|titre numéro=|jour=8|mois=août|année=2005|pages=1-19|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_specnervsys/specnervsys.html|doi=10.1895/wormbook.1.12.1| consulté le=26 décembre 2010|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Au début des années 1970, du fait de sa simplicité et de sa facilité d’élevage, [[Sydney Brenner]] le choisit comme [[organisme modèle]] pour ses travaux sur le processus de régulation génétique du développement qui lui valurent un Prix Nobel en [[2002]]<ref>{{en}} {{Lien web|url=http://elegans.swmed.edu/Sydney.html |titre=Sydney Brenner |id= |série= |auteur= |lien auteur= |coauteurs= |date= |année=1987 |mois= |site= |éditeur= |isbn= |page= |citation= |en ligne le= |consulté le=26 décembre 2010 }}</ref>. Pour ses travaux, Brenner et son équipe ont découpé les vers en milliers de sections ultra fines et photographié chacune d'entre elles au [[Microscopie électronique|microscope électronique]] afin de visualiser les fibres assorties à chaque section et ainsi planifier chaque neurone et chaque synapse dans le corps du ver<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=J. G.|nom1=White|lien auteur1=|prénom2=E.|nom2=Southgate|lien auteur2=|prénom3=J. N.|nom3=Thomson|lien auteur3=|prénom4=S.|nom4=Brenner|lien auteur4=Sydney Brenner|traduction=|titre=The Structure of the Nervous System of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans|sous-titre=|périodique=Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B|lien périodique=Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=314|titre volume=|numéro=1165|titre numéro=|jour=12|mois=novembre|année=1986|pages=1-340|issn=1471-2970|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1098/rstb.1986.0056| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Actuellement, un tel niveau de détail n'est disponible pour aucun autre organisme, et les informations récoltées ont rendu possibles de nombreuses études. | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Vertébrés === | ||

| - | [[Image:Brains-fr.svg|thumb|Comparaison des cerveaux de différentes espèces]] | ||

| - | Apparus il y a 500 millions d'années, les [[vertébrés]] ont dérivé d'une forme proche de la [[myxine]] actuelle<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=D.-G.|nom1=Shu|lien auteur1=|prénom2=S.|nom2=Conway Morris|lien auteur2=|prénom3=J.|nom3=Han|lien auteur3=|prénom4=Z.-F.|nom4=Zhang|lien auteur4=|prénom5=K.|nom5=Yasui|lien auteur5=|prénom6=P.|nom6=Janvier|lien auteur6=|prénom7=L.|nom7=Chen|lien auteur7=|prénom8=X.-L.|nom8=Zhang|lien auteur8=|prénom9=J.-N|nom9=Liu|lien auteur9=|prénom10=Y.|nom10=Li|lien auteur10=|prénom11=H.-Q|nom11=Liu|lien auteur11=|traduction=|titre=Head and backbone of the Early Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys|sous-titre=|périodique=Nature|lien périodique=Nature (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=421|titre volume=|numéro=6922|titre numéro=|jour=30|mois=janvier|année=2003|pages=526-529|issn=0028-0836|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1038/nature01264| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Le cerveau de tous les vertébrés présente fondamentalement la même structure<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=fr|prénom1=R.|nom1=Eckert|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=D.|nom2=Randall|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=F. Math|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Physiologie animale|sous-titre=Mécanismes et adaptations|titre original=|numéro d'édition=4|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=De Boeck Université|éditeur=De Boeck Université|lieu=|année=1999|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=822|format=|isbn=9782744500534|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=415|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=OaSHXG2liFgC&dq=Physiologie+animale+:+m%C3%A9canismes+et+adaptations&source=gbs_navlinks_s|lire en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=OaSHXG2liFgC&lpg=PP1&dq=Physiologie%20animale%20%3A%20m%C3%A9canismes%20et%20adaptations&pg=PA415#v=onepage&q&f=false|consulté le={{1er}} janvier 2011|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Au cours de l'évolution de cet embranchement, la tendance évolutive du cerveau a été de suivre un gradient de taille et de complexité croissante, en particulier chez les [[mammifères]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=G. F.|nom1=Striedter|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Principles of brain evolution|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Sinauer Associates|lieu=|année=2005|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=436|format=|isbn=9780878938209|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=JzdmQgAACAAJ&dq=isbn:9780878938209&ei=ET4fTYLeDoOsywSA4JXrCw&cd=1|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau des vertébrés est d'un [[tissu mou]] et d'une texture [[gélatine]]use<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=E. R.|nom1=Kandel|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=J. H.|nom2=Schwartz|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=T. M.|nom3=Jessell|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Principles of neural science|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=4|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=McGraw-Hill|éditeur=McGraw-Hill|lieu=|année=2000|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=1414|format=|isbn=9780838577011|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=17|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=yMtpAAAAMAAJ&dq=isbn:9780838577011&ei=-j4fTejhBNPaUM_hzZYI&cd=1|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=Kandel|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. De manière générale, le tissu cérébral vivant est rosâtre à l'extérieur et blanchâtre à l'intérieur. Le cerveau des vertébrés est enveloppé d'un [[Membrane (biologie)|système membranaire]] de [[tissu conjonctif]], les [[méninge]]s, qui sépare le [[crâne]] du cerveau<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=A.|nom1=Parent|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=M. B.|nom2=Carpenter|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Carpenter's human neuroanatomy|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=9|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Williams & Wilkins|lieu=|année=1996|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=1011|format=|isbn=9780683067521|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=1|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=IJ5pAAAAMAAJ&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. De l'extérieur vers l'intérieur, les méninges sont composées de trois membranes : la [[dure-mère]], l'[[arachnoïde]] et la [[pie-mère]]. L'arachnoïde et la pie-mère sont étroitement connectées entre elles et peuvent ainsi être considérées comme une seule et même couche, la pie-arachnoïde. Compris entre l'arachnoïde et la pie mère, l'espace sous-arachnoïdien contient le [[liquide cérébro-spinal]] qui circule dans l'étroit espace entre les cellules et à travers les cavités appelées [[système ventriculaire]]. Ce liquide sert notamment de protection mécanique au cerveau en absorbant et amortissant les chocs et à transporter [[hormone]]s et [[nutriment]]s vers le tissu cérébral. Les [[Vaisseau sanguin|vaisseaux sanguins]] viennent irriguer le [[système nerveux central]] à travers l'espace périvasculaire au-dessus de la pie-mère. Au niveau des vaisseaux sanguins, les cellules sont étroitement jointes, formant la [[barrière hémato-encéphalique]] qui protège le cerveau en agissant comme un [[filtre]] vis-à-vis des [[toxine]]s susceptibles d'être contenues dans le [[sang]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Tous les cerveaux des vertébrés possèdent la même forme sous-jacente observable par la manière dont le cerveau se développe<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | p=1019 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Pendant le [[neurodéveloppement]], le système nerveux commence à se mettre en place par l'apparition d'une fine bande de tissu neural parcourant tout le [[dos]] de l'[[embryon]]. La bande s'épaissit ensuite et se plisse pour former le [[tube neural]]. C'est à l'extrémité crânienne du tube que se développe le cerveau, l'émergence de ce crâne chez les premiers vertébrés aquatiques étant en relation avec le développement de leur sens de l'[[olfaction]] lié à leur capacités exploratrices à la recherche de proies. Au départ, le cerveau se manifeste comme trois gonflements qui représentent en fait le [[prosencéphale]], le [[mésencéphale]] et le [[rhombencéphale]]. Chez de nombreux groupes de vertébrés, ces trois régions gardent la même taille chez l'adulte, mais le prosencéphale des mammifères devient plus important que les autres régions et le mésencéphale plus petit<ref name="Vincent">{{ouvrage|auteur=[[Jean-Didier Vincent]] Pierre-Marie Liedo|titre=Le cerveau sur mesure|éditeur=Odile Jacob|date=2012|pages totales=290|isbn=2738127096|lire en ligne=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | La relation entre la taille du cerveau, la taille de l'organisme et d'autres facteurs a été étudiée à travers un grand nombre d'espèces de vertébrés. La taille du cerveau augmente avec la taille de l'organisme, mais pas de manière proportionnelle. Chez les mammifères, la relation suit une [[loi de puissance]], avec un [[Exposant (mathématiques)|exposant]] d'environ 0,75<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=E.|nom1=Armstrong|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction= |titre= | ||

| - | Relative Brain Size and Metabolism in Mammals | ||

| - | |sous-titre=|périodique=Science|lien périodique=Science (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=220|titre volume=|numéro=4603|titre numéro=|jour=17|mois=juin|année=1983|pages=1302-1304|issn=0036-8075|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1126/science.6407108| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Cette formule s'applique pour le cerveau moyen des mammifères mais chaque famille s'en démarque plus ou moins, reflétant la complexité de leur comportement. Ainsi, les [[primates]] ont un cerveau cinq à dix fois plus gros que ce qu’indique la formule. De manière générale, les [[Prédation|prédateurs]] tendent à avoir des cerveaux plus gros. Quand le cerveau des mammifères augmente en taille, toutes les parties n'augmentent pas dans la même proportion. Plus le cerveau d'une espèce est gros, plus la fraction occupée par le [[cortex]] est importante<ref name="finlay">{{article|langue=en|prénom1=B. L.|nom1=Finlay|lien auteur1=|prénom2=R. B.|nom2=Darlington|lien auteur2=|prénom3=N.|nom3=Nicastro|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Developmental structure in brain evolution|sous-titre=|périodique=Behav. Brain Sci.|lien périodique=Behavioral and Brain Sciences|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=24|titre volume=|numéro=2|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=|année=2001|pages=263-278|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1017/S0140525X01003958| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>, 80% de l'activité cérébrale dépendant des signaux visuels chez les primates<ref name="Vincent"/>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | ==== Régions du cerveau ==== | ||

| - | |||

| - | En [[neuroanatomie]] des vertébrés, le cerveau est généralement considéré comme constitué de six régions principales définies sur la base du développement du système nerveux à partir du [[tube neural]] : le [[télencéphale]], le [[diencéphale]], le [[mésencéphale]], le [[cervelet]], le [[Pont (système nerveux)|pont]], et le [[bulbe rachidien]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 17 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Chacune de ces régions possède une structure interne complexe. Certaines régions du cerveau, comme le [[cortex cérébral]] ou le cervelet, sont formés de couches formant des replis sinueux, les [[Circonvolution cérébrale|circonvolutions cérébrales]], qui permettent d'augmenter la surface corticale tout en logeant dans la boîte crânienne. Les autres régions du cerveau représentent des groupes de nombreux [[Noyau (biologie)|noyaux]]. Si des distinctions claires peuvent être établies à partir de la structure neurale, la chimie et la connectivité, des milliers de régions distinctes peuvent être identifiées dans le cerveau des vertébrés. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chez plusieurs branches des vertébrés, l'évolution a amené des changements importants sur l'architecture du cerveau. Les composants du cerveau des [[requin]]s sont assemblés de façon simple et directe, mais chez les [[Téléostéens|poissons téléostéens]], groupe majoritaire des poissons modernes, le [[prosencéphale]] est devenu [[wikt:éverté|éverté]]. Le cerveau des oiseaux présente également d'importants changements<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=R. G.|nom1=Northcutt|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Forebrain evolution in bony fishes|sous-titre=|périodique=Brain Res. Bull.|lien périodique=Brain Research Bulletin|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=75|titre volume=|numéro=2-4|titre numéro=|jour=18|mois=mars|année=2008|pages=191-205|issn=0361-9230|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.058| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Un des principaux composants du prosencéphale des oiseaux, la crête ventriculaire dorsale, a longtemps été considéré comme l'équivalent du [[Ganglions de la base|ganglion basal]] des mammifères, mais est maintenant considéré comme étroitement apparenté au [[néocortex]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=A.|nom1=Reiner|lien auteur1=|prénom2=K.|nom2=Yamamoto|lien auteur2=|prénom3=H. J.|nom3=Karten|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Organization and evolution of the avian forebrain|sous-titre=|périodique=Anat. Rec.|lien périodique=Anat. Rec.|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=287A|titre volume=|numéro=1|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=novembre|année=2005|pages=1080–1102|issn=1932-8494|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi=10.1002/ar.a.20253|pmid=16206213| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | De nombreuses régions du cerveau ont gardé les mêmes propriétés chez tous les vertébrés<ref name=shepherd />. Le rôle de la plupart de ces régions est encore soumis à la discussion mais il est malgré tout possible de dresser une liste des régions principales du cerveau et le rôle qu'on leur attribue selon les connaissances actuelles : | ||

| - | |||

| - | [[Image:Vertebrate-brain-regions.png|vignette|Les principales divisions de l'encéphale représentées sur un cerveau de [[requin]] et un cerveau humain]] | ||

| - | |||

| - | * Le [[bulbe rachidien]] (ou ''medulla oblongata'') prolonge la [[moelle épinière]]. Elle contient de nombreux petits [[Noyau (biologie)|noyaux]] impliqués dans un grand nombre de fonctions [[Mouvement (anatomie)|motrices]] et [[Sens (physiologie)|sensitives]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 44-45 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * L'[[hypothalamus]] est un petit [[organe]] situé sous le [[prosencéphale]]. Il est composé de nombreux petits noyaux possédant chacun ses propres connexions et une [[neurochimie]] particulière. L'hypothalamus régule et contrôle de nombreuses fonctions biologiques essentielles telles que l'[[Sommeil|éveil]] et le [[sommeil]], la [[faim]] et la [[soif]], ou la libération d'[[hormone]]s<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=D. F.|nom1=Swaab|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=The human hypothalamus|sous-titre=Handbook of clinical neurology. Neuropathology of the human hypothalamus and adjacent brain structure|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Elsevier Science|éditeur=Elsevier Health Sciences|lieu=|année=2004|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=2|titre volume=|pages totales=597|format=|isbn=9780444514905|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=Js81Pr1PmaAC&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Le [[thalamus]] est également composé de noyaux aux fonctions diverses. Une partie d'entre eux servent à relayer l'information entre les [[Hémisphère cérébral|hémisphères cérébraux]] et le [[tronc cérébral]]. D'autres sont impliqués dans la [[motivation]]. La ''[[zona incerta]]'', ou région sous-thalamique, semble jouer un rôle dans plusieurs comportements élémentaires comme la [[faim]], la [[soif]], la [[défécation]] et la [[copulation]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=E. G.|nom1=Jones|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=The thalamus|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Springer Verlag|éditeur=Plenum Press|lieu=|année=1985|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=935|format=|isbn=9780306418563|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=WMxqAAAAMAAJ&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Le [[cervelet]] joue un rôle majeur dans la coordination des mouvements en modulant et optimisant les informations provenant d'autres régions cérébrales afin de les rendre plus précises. Cette précision n'est pas acquise à la naissance et s'apprend avec l'[[expérience]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 42 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Le [[tectum]], partie supérieure du [[mésencéphale]], permet de diriger les actions dans l'espace et de conduire le mouvement. Chez les mammifères, l'aire du tectum la plus étudiée est le [[colliculus supérieur]] qui s'occupe de diriger le mouvement des [[yeux]]. Le tectum reçoit de nombreuses informations visuelles, mais aussi les informations d'autres sens qui peuvent être utiles pour diriger les actions comme l'[[ouïe]]. Chez certains poissons, comme la [[lamproie]], le tectum occupe la plus large partie du cerveau<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=K.|nom1=Saitoh|lien auteur1=|prénom2=A.|nom2=Ménard|lien auteur2=|prénom3=S.|nom3=Grillner|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Tectal control of locomotion, steering, and eye movements in lamprey|sous-titre=|périodique=J. Neurophysiol.|lien périodique=Journal of Neurophysiology|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=97|titre volume=|numéro=4|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=avril|année=2007|pages=3093-3108|issn=0022-3077|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://jn.physiology.org/content/97/4/3093.full.pdf|pmid = 17303814|doi=10.1152/jn.00639| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Le [[Pallium (anatomie)|pallium]] est une couche de [[Substance grise|matière grise]] qui s'étale sur la surface du [[prosencéphale]]. Chez les mammifères et les reptiles, il est appelé [[cortex cérébral]]. Le pallium est impliqué dans de nombreuses fonctions telles que l'[[olfaction]] et la [[Mémoire (psychologie)|mémoire spatiale]]. Chez les mammifères, il s'agit de la région dominante du cerveau et elle [[wikt:subsumer|subsume]] les fonctions de nombreuses [[Sous-cortical|régions sous-corticales]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=L.|nom1=Puelles|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Thoughts on the development, structure and evolution of the mammalian and avian telencephalic pallium|sous-titre=|périodique=Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B|lien périodique=Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=356|titre volume=|numéro=1414|titre numéro=|jour=29|mois=octobre|année=2001|pages=1583-1598|issn=0962-8436|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/356/1414/1583.full.pdf|pmid=11604125 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2001.0973| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * L'[[Hippocampe (cerveau)|hippocampe]], au sens strict, n'est présent que chez les mammifères. Néanmoins, cette région dérive du pallium médial communs à tous les vertébrés. Sa fonction est encore mal connue mais cette partie du cerveau intervient dans la mémoire spatiale et la navigation<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=C.|nom1=Salas|lien auteur1=|prénom2=C.|nom2=Broglio|lien auteur2=|prénom3=F.|nom3=Rodríguez|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Evolution of Forebrain and Spatial Cognition in Vertebrates: Conservation across Diversity|sous-titre=|périodique=Brain Behav. Evol.|lien périodique=Brain Behavior and Evolution|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=62|titre volume=|numéro=2|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=|année=2003|pages=72-82|issn= 0006-8977|issn2=1421-9743|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|doi = 10.1159/000072438| pmid = 12937346| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Les [[ganglions de la base]] sont un groupe de structures interconnectées situées dans le prosencéphale. La fonction principale de ces ganglions semble être la [[sélection de l'action]]. Ils envoient des signaux inhibiteurs à toutes les parties du cerveau qui peuvent générer des actions et, dans les bonnes circonstances, peuvent lever l'inhibition afin de débloquer le processus et permettre l'exécution de l'action. Les [[Système de récompense|récompenses]] et les [[punition]]s exercent leurs plus importants effets neuraux au niveau des ganglions de la base<ref>{{article|langue=|prénom1=S.|nom1=Grillner|lien auteur1=|prénom2=J.|nom2=Hellgren|lien auteur2=|prénom3=A.|nom3=Ménard|lien auteur3=|prénom4=K.|nom4=Saitoh|lien auteur4=|prénom5=M. A.|nom5=Wikström|lien auteur5=|traduction=|titre=Mechanisms for selection of basic motor programs – roles for the striatum and pallidum|sous-titre=|périodique=Trends Neurosci.|lien périodique=Trends in Neurosciences|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=28|titre volume=|numéro=7|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=juillet|année=2005|pages=364-370|issn=0166-2236|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid = 15935487|doi=10.1016/j.tins.2005.05.004 | consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | * Le [[bulbe olfactif]] est une structure particulière qui traite les signaux olfactifs et envoie l'information vers la zone olfactive du pallium. Chez beaucoup de vertébrés, le bulbe olfactif est très développé mais il est plutôt réduit chez les [[Primates]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=R. G.|nom1=Northcutt|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Evolution of the Telencephalon in Nonmammals|sous-titre=|périodique=Ann. Rev. Neurosci.|lien périodique=Annual Review of Neuroscience|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=4|titre volume=|numéro=|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=mars|année=1981|pages=301-350|issn= 0147-006X|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=7013637|doi=10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.001505| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | {{clr}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | ==== Mammifères ==== | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le [[cortex cérébral]] est la région du cerveau qui distingue au mieux le cerveau des [[Mammifères]] de celui des autres [[Vertébrés]], celui des [[Primates]] de celui des autres Mammifères, et celui des [[Homme (espèce)|Hommes]] de celui des autres Primates. Le [[rhombencéphale]] et le [[mésencéphale]] des Mammifères est généralement similaire à celui des autres vertébrés, mais des différences très importantes se manifestent au niveau du [[prosencéphale]] qui n'est pas seulement beaucoup plus gros mais présente également des modifications dans sa structure<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=R. A.|nom1=Barton|lien auteur1=|prénom2=P. H.|nom2=Harvey|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Mosaic evolution of brain structure in mammals|sous-titre=|périodique=Nature|lien périodique=Nature (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=405|titre volume=|numéro=6790|titre numéro=|jour=29|mois=juin|année=2000|pages=1055-1058|issn=0028-0836|issn2=1476-4687|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=10890446|doi=10.1038/35016580| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Chez les autres vertébrés, la surface du [[télencéphale]] est recouverte d'une simple couche, le [[pallium (anatomie)|pallium]]<ref name=aboitiz>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=F.|nom1=Aboitiz|lien auteur1=|prénom2=D.|nom2=Morales |lien auteur2=|prénom3=J.|nom3=Montiel |lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=The evolutionary origin of the mammalian isocortex: Towards an integrated developmental and functional approach|sous-titre=|périodique= Behav. Brain Sci.|lien périodique= Behavioral and Brain Sciences|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=26|titre volume=|numéro=5|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=|année=2003|pages=535-552|issn=0140-525X|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=15179935|doi=10.1017/S0140525X03000128| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Chez les Mammifères, le pallium a évolué en une couche à six feuillets appelée [[néocortex]]. Chez les Primates, le néocortex s'est grandement élargi, notamment au niveau de la région des [[Lobe frontal|lobes frontaux]]. L'[[Hippocampe (cerveau)|hippocampe]] des mammifères a également une structure bien particulière. | ||

| - | |||

| - | L'histoire évolutive de ces particularités mammaliennes, notamment le néocortex, est difficile à retracer<ref name=aboitiz />. Les [[synapsides]], ancêtres des Mammifères, se sont séparés des [[sauropsides]], ancêtres des [[reptiles]] actuels et des [[oiseaux]], il y a environ 350 millions d'années. Ensuite, il y a 120 millions d'années, les mammifères se sont ramifiés en [[monotrèmes]], [[marsupiaux]] et [[placentaires]], division qui a abouti aux représentants actuels. Le cerveau des monotrèmes et des marsupiaux se distingue de celui des placentaires (groupe majoritaire des Mammifères actuels) à différents niveaux, mais la structure de leur cortex cérébral et de leur hippocampe est la même. Ces structures ont donc probablement évolué entre -350 et -120 millions d'années, une période qui ne peut être étudiée qu'à travers les [[fossile]]s mais ceux-ci ne préservent pas les tissus mous comme le cerveau. | ||

| - | |||

| - | ==== Primates ==== | ||

| - | [[Image:Skull and brain normal human.svg|thumb|Schéma d'un cerveau humain dans sa boite crânienne.]] | ||

| - | Le cerveau des primates possède la même structure que celui des autres mammifères, mais il est considérablement plus large proportionnellement à la taille de l'organisme<ref name="finlay"/>. Cet élargissement provient essentiellement de l'expansion massive du [[cortex]], notamment au niveau des régions servant à la [[Vue|vision]] et à la [[prévoyance]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=W. H.|nom1=Calvin|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=How brains think|sous-titre=Evolving intelligence, then and now|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=Science masters series|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Basic Books|lieu=|année=1997|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=192|format=|isbn=9780465072781|isbn2=046507278X|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=z1r03ECL5A8C&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Le processus de perception visuelle chez les Primates est très complexe, faisant intervenir au moins trente zones distinctes et un important réseau d'interconnexions, et occupe plus de la moitié du néorcortex<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=M. I.|nom1=Sereno|lien auteur1=|prénom2=A. M.|nom2=Dale|lien auteur2=|prénom3=J. B.|nom3=Reppas|lien auteur3=|prénom3=J. B.|nom3=Reppas|lien auteur3=|prénom4=K. K.|nom4=Kwong|lien auteur4=|prénom5=J. W.|nom5=Belliveau|lien auteur5=|prénom6=T. J.|nom6=Brady|lien auteur6=|prénom7=B. R.|nom7=Rosen|lien auteur7=|prénom8=R. B.|nom8=Tootell|lien auteur8=|traduction=|titre=Borders of multiple visual areas in humans revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging|sous-titre=|périodique=Science|lien périodique=Science (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=268|titre volume=|numéro=5212|titre numéro=|jour=12|mois=mai|année=1995|pages=889-893 |issn=0036-8075|issn2=1095-9203|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://www.cogsci.ucsd.edu/~sereno/papers/HumanRetin95.pdf|pmid=7754376|doi=10.1126/science.7754376| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=Over half of the neocortex in non-human primates is occupied by visual areas. At least 25 visual areas beyond the primary visual cortex (V1) have been identified with a combination of microelectrode mapping, tracer injections, histological stains, and functional studies|id=}}</ref>. L'élargissement du cerveau provient également de l'élargissement du [[cortex préfrontal]] dont les fonctions sont difficilement résumables mais portent sur la [[planification]], la [[mémoire de travail]], la [[motivation]], l'[[attention]], et les [[fonctions exécutives]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chez les humains, l'élargissement des lobes frontaux est encore plus extrême, et d'autres parties du cortex sont également devenues plus larges et complexes. | ||

| - | |||

| - | == Histologie == | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le [[Tissu biologique|tissu]] cérébral est composé de deux types de [[Cellule (biologie)|cellules]], les [[neurone]]s et les [[Cellule gliale|cellules gliales]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | p=20 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Les neurones jouent un rôle prépondérant dans le traitement de l'information nerveuse tandis que les cellules gliales, ou cellules de soutien, assurent diverses fonctions annexes dont le [[métabolisme]] cérébral. Bien que ces deux types de cellules soient en même quantité dans le cerveau, les cellules gliales sont quatre fois plus nombreuses que les neurones dans le [[cortex cérébral]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=F. A. C.|nom1=Azevedo|lien auteur1=|prénom2=L. R. B.|nom2=Carvalho|lien auteur2=|prénom3=L. T.|nom3=Grinberg|lien auteur3=|prénom4=J. M.|nom4=Farfel|lien auteur4=|prénom5=R. E. L.|nom5=Ferretti|lien auteur5=|prénom6=R. E. P.|nom6=Leite|lien auteur6=|prénom7=W. J.|nom7=Filho|lien auteur7=|prénom8=R.|nom8=Lent|lien auteur8=|prénom9=s.|nom9=Herculano-Houzel|lien auteurç=|traduction=|titre=Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain|sous-titre=|périodique=J. Comp. Neurol.|lien périodique=Journal of Comparative Neurology|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=513|titre volume=|numéro=5|titre numéro=|jour=10|mois=avril|année=2009|pages=532–541|issn=1096-9861|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=19226510 |doi=10.1002/cne.21974| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Contrairement aux cellules gliales, les neurones sont capables de communiquer entre eux à travers de longues distances<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | p=21 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Cette communication se fait par des signaux envoyés par le biais de l'[[axone]], prolongement [[Protoplasme|protoplasmique]] du neurone qui s'étend depuis le corps cellulaire, se ramifie et se projette, parfois vers des zones proches, parfois vers des régions plus éloignées du cerveau ou du corps. Le prolongement de l'axone peut être considérable chez certains neurones. Les signaux transmis par l'axone se font sous forme d'influx électrochimiques, appelés [[Potentiel d'action|potentiels d'action]], qui durent moins d'un millième de [[seconde (temps)|seconde]] et traversent l'axone à une [[vitesse]] de 1 à 100 [[mètre]]s par seconde. Certains neurones émettent en permanence des potentiels d'action, de 10 à 100 par seconde, d'autres n'émettent des potentiels d'action qu'occasionnellement. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le point de jonction entre l'axone d'un neurone et un autre neurone, ou une cellule non-neuronale, est la [[synapse]] où le signal est transmis<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 10 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Un axone peut avoir jusqu'à plusieurs milliers de terminaisons synaptiques. Lorsque le potentiel d'action, après avoir parcouru l'axone, parvient à la synapse, cela provoque la libération d'un agent chimique appelé [[neurotransmetteur]]. Une fois libéré, le neurotransmetteur se lie aux [[Récepteur membranaire|récepteurs membranaires]] de la cellule cible. Certains récepteurs neuronaux sont excitateurs, c'est-à-dire qu'ils augmentent la fréquence de potentiel d'action au sein de la cellule cible ; d'autres récepteurs sont inhibiteurs et diminuent la fréquence de potentiel d'action ; d'autres ont des effets modulatoires complexes. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Les axones occupent la majeure partie de l'espace cérébral<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 2 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Les axones sont souvent regroupés en larges groupes pour former des faisceaux de fibres nerveuses. De nombreux axones sont enveloppés d'une gaine de [[myéline]], une substance qui permet d'augmenter fortement la vitesse de propagation du potentiel d'action. La myéline est de couleur [[blanc]]he, de telle sorte que les régions du cerveau essentiellement occupées par ces fibres nerveuses apparaissent comme de la [[substance blanche]] tandis que les zones densément peuplées par les corps cellulaires des neurones apparaissent comme de la [[substance grise]]. La [[longueur]] totale des axones myélinisés dans le cerveau adulte d'un Humain dépasse en moyenne les 100 000 [[kilomètre]]s<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=L.|nom1=Marner|lien auteur1=|prénom2=J. R.|nom2=Nyengaard|lien auteur2=|prénom3=Y.|nom3=Tang|lien auteur3=|prénom4=B.|nom4=Pakkenberg|lien auteur4=|traduction=|titre=Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age|sous-titre=|périodique=J. Comp. Neurol.|lien périodique=Journal of Comparative Neurology|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=462|titre volume=|numéro=2|titre numéro=|jour=21|mois=juillet|année=2003|pages=144-152|issn=1096-9861|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=12794739|doi=10.1002/cne.10714| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | == Développement == | ||

| - | |||

| - | [[Fichier:EmbryonicBrain.svg|thumb|Principales subdivisions du cerveau embryonnaire des Vertébrés.]] | ||

| - | Le [[développement]] du cerveau suit une succession d'étapes<ref name=purves>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=D.|nom1=Purves|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=J. W.|nom2=Lichtman|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Principles of neural development|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Sinauer Associates|lieu=|année=1985|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=433|format=|isbn=9780878937448|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=1|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=t9JqAAAAMAAJ&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=Purves|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Beaucoup de neurones naissent dans des zones spécifiques contenant des [[Cellule souche|cellules souches]] et migrent ensuite à travers le tissu pour atteindre leur destination ultime<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Purves | 1985 | loc=ch. 4 |id=Purves}}</ref>. Ainsi, dans le [[Cortex cérébral|cortex]], la première étape du développement est la mise en place d'une armature par un type de [[cellule gliale|cellules gliales]], les [[cellule radiale|cellules radiales]], qui établissent des fibres verticales à travers le cortex. Les nouveaux neurones corticaux sont créés à la base du cortex et « grimpent » ensuite le long des fibres radiales jusqu'à atteindre les couches qu'ils sont destinés à occuper. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chez les vertébrés, les premières étapes du développement sont communes à toutes les espèces<ref name=purves />. Tandis que l'embryon passe d'une forme ronde à une structure de type vermiforme, une étroite bande de l'[[ectoderme]] se décolle de la ligne médiane dorsale pour devenir la [[plaque neurale]], précurseur du [[système nerveux]]. La plaque neurale se creuse, s'[[wikt:invaginer|invagine]] de manière à former la [[gouttière neurale]] puis, les [[pli neural|plis neuraux]] qui bordent la gouttière fusionnent pour fermer la gouttière qui devient le [[tube neural]]. Ce tube se subdivise ensuite en une partie antérieure renflée, la vésicule céphalique primitive, qui se segmente en trois [[Vésicule (biologie)|vésicules]] qui deviendront le [[prosencéphale]], le [[mésencéphale]], et le [[rhombencéphale]]<ref name=purves />. Le prosencéphale se divise ensuite en deux autres vésicules, le [[télencéphale]] et le [[diencéphale]] tandis que le rhombencéphale se divise en [[métencéphale]] et [[myélencéphale]]. Chacune de ses vésicules contient des zones prolifératives dans lesquelles [[neurone]]s et [[Cellule gliale|cellules gliales]] sont formés. Ces deux types de cellules migrent ensuite, parfois sur de longues distances, vers leurs positions finales. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Une fois qu'ils sont en place, les neurones commencent à étendre leurs [[Dendrite (biologie)|dendrites]] et leur [[axone]] autour d'eux<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Purves | 1985 | loc=ch. 5 et 7 |id=Purves}}</ref>. L'axone doit généralement s'étendre sur une longue distance à partir du corps cellulaire du neurone et doit se connecter sur des cibles bien spécifiques, ce qui lui nécessite de croître d'une manière plus complexe. À l'extrémité de l'axone en développement se trouve une région parsemée de [[Récepteur (cellule)|récepteurs]] [[Chimie|chimiques]], le cône de croissance. Ces récepteurs recherchent des signaux moléculaires dans l'environnement alentour qui guident la croissance de l'axone en attirant ou en repoussant le cône de croissance et dirigent ainsi l'étirement de l'axone dans une direction donnée. Le cône de croissance navigue ainsi à travers le cerveau jusqu'à ce qu'il atteigne sa région de destination, où d'autres signaux chimiques engendrent la formation de [[synapse]]s. Des milliers de [[gène]]s interviennent pour générer ces signaux de guidage mais le réseau synaptique qui en émerge n'est déterminé qu'en partie par les [[gène]]s. Dans de nombreuses parties du cerveau, les axones connaissent d'abord une surcroissance proliférative qui est ensuite régulée par des mécanismes dépendants de l'activité neuronale<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Purves | 1985 | loc=ch. 12 |id=Purves}}</ref>. Ce processus sophistiqué de sélection et d'ajustement graduel aboutit finalement à la forme adulte du réseau neuronal. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chez de nombreux mammifères, dont l'Homme, les neurones sont crées principalement avant la [[naissance]], et le cerveau du [[nouveau-né]] contient substantiellement plus de neurones que celui de l'[[adulte]]. A noter que notre cerveau utilise que 12,6% des neurones en moyenne. Cependant quelques zones continuent de générer de nouveaux neurones tout au long de la vie, telles que le [[bulbe olfactif]] ou le ''gyrus dentatus'' de l'[[Hippocampe (cerveau)|hippocampe]]. En dehors de ces exceptions, le nombre de neurones présents à la naissance est définitif, contrairement aux cellules gliales qui sont renouvelées tout au long de la vie, à la manière de la plupart des cellules de l'organisme. Bien que le nombre de neurones évolue peu après la naissance, les connexions axonales continuent de se développer et de s'organiser pendant encore un long moment. Chez l'Homme ce processus n'est pas terminé avant l'[[adolescence]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | De nombreuses questions restent en suspens concernant ce qui relève de l'[[inné]] et de l'[[acquis]] à propos de l'[[esprit]], de l'[[intelligence]] et de la [[personnalité]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=M.|nom1=Ridley|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=The agile gene|sous-titre=How nature turns on nurture|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Forth Estate|lieu=|année=2004|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=352|format=|isbn=9780060006792|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=9TkUHQAACAAJ&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Bien que de nombreux points restent à éclaircir, la [[neuroscience]] a montré que deux facteurs sont essentiels. D'un côté, les gènes déterminent la forme générale du cerveau, et la manière dont le cerveau répond à l'expérience. D'un autre côté, l'expérience est nécessaire pour affiner la matrice de connexions synaptiques. À bien des égards, la qualité et la quantité d'expériences joue un rôle<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=T. N.|nom1=Wiesel|lien auteur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Postnatal development of the visual cortex and the influence of environment|sous-titre=|périodique=Nature|lien périodique=Nature (revue)|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=299|titre volume=|numéro=5884|titre numéro=|jour=14|mois=octobre|année=1982|pages=583-591|issn=0028-0836|issn2=1476-4687|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1981/wiesel-lecture.pdf|pmid=6811951|doi=10.1038/299583a0| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. L’[[Enrichissement environnemental (système neural)|enrichissement environnemental]] montre que le cerveau d'un animal placé dans un environnement plus riche et stimulant a un nombre plus important de synapses que celui d'un animal dans un milieu plus pauvre<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=H.|nom1=van Praag|lien auteur1=|prénom2=G.|nom2=Kempermann|lien auteur2=|prénom3=F. H.|nom3=Gage|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Neural consequences of enviromental enrichment|sous-titre=|périodique=Nat. Rev. Neurosci.|lien périodique=Nature Reviews Neuroscience|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=1|titre volume=|numéro=3|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=décembre|année=2000|pages=191-198|issn=1471-003X|issn2=1471-0048|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=|pmid=11257907|doi=10.1038/35044558| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | == Fonctions == | ||

| - | |||

| - | La principale fonction du cerveau est de contrôler les actions de l'organisme à partir des [[Sens (physiologie)|informations sensorielles]] qui lui parviennent<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=T. J.|nom1=Carew|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Behavioral neurobiology|sous-titre=The cellular organization of natural behavior|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Sinauer Associates|lieu=|année=2000|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=435|format=|isbn=9780878930920|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=1|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=wEMTGwAACAAJ&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. Les signaux sensoriels peuvent stimuler une réponse immédiate, moduler un schéma d'activité en cours, ou être emmagasinés pour un besoin futur. Ainsi, par le rôle central qu'il exerce dans la captation des [[stimulus|stimuli]] externes, le cerveau occupe le rôle central dans la création de réponses à l'environnement. Le cerveau a aussi un rôle dans la [[Hormone|régulation hormonale]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau des vertébrés reçoit des signaux par les nerfs afférents de la part des différentes régions de l'organisme. Le cerveau interprète ces signaux et en tire une réponse fondée sur l'intégration des signaux électriques reçus, puis la transmet. Ce jeu de réception, d'intégration, et d'émission de signaux représente la fonction majeure du cerveau, qui explique à la fois les [[Sens (physiologie)|sensations]], le [[Mouvement (anatomie)|mouvement]], la [[mémoire (sciences humaines)|mémoire]] et, on le suppose, la [[conscience]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Pour mener à bien sa complexe tâche, le cerveau est organisé en sous-systèmes fonctionnels c'est-à-dire que certaines régions cérébrales traitent plus spécifiquement certains aspects de l'information. Cette division fonctionnelle n'est pas stricte et ces sous-systèmes peuvent être catégorisés de plusieurs façons : anatomiquement, chimiquement ou fonctionnellement. Une de ces catégorisations repose sur les [[neurotransmetteurs]] chimiques utilisés par les neurones pour communiquer. Une autre se base sur la manière dont chaque zone du cerveau contribue au traitement de l'information : les zones sensorielles amènent l'information au cerveau ; les signaux moteurs envoient l'information du cerveau jusqu'aux [[muscle]]s et aux [[glande]]s ; les systèmes excitateurs modulent l'activité du cerveau en fonction du moment de la journée et de divers facteurs. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau utilise principalement le [[glucose]] comme [[Énergie|substrat énergétique]] et une [[perte de conscience]] peut survenir s'il en manque. La consommation énergétique du cerveau n'est pas particulièrement variable, mais les régions actives du cortex consomment plus d'énergie que les inactives. | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Systèmes de neurotransmissions === | ||

| - | {{Voir aussi|Neuromodulation}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | Selon le [[principe de Dale]], chaque neurone du cerveau libère constamment le même [[neurotransmetteur]] chimique, ou la même combinaison de neurotransmetteurs, pour toutes les connexions synaptiques qu'il entretient avec d'autres neurones<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 15 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Un neurone peut donc être caractérisé en fonction des neurotransmetteurs qu'il libère bien qu'il existe quelques exceptions à ce principe. Les deux neurotransmetteurs les plus fréquents sont le [[glutamate]], qui correspond généralement à un signal excitatoire, et l'[[acide γ-aminobutyrique]] (GABA), généralement inhibitoire. Les neurones utilisant ces deux neurotransmetteurs se retrouvent dans presque toutes les régions du cerveau et forment un large pourcentage des synapses du cerveau<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=P. L.|nom1=McGeer|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=E. G.|nom2=McGeer|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Basic neurochemistry|sous-titre=Molecular, cellular and medical aspects |titre original=|numéro d'édition=4|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=Raven Press|lieu=New York|année=1989|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=984|format=|isbn=9780881673432|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=15|titre chapitre=Amino acid neurotransmitters|passage=311-332|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=b-FqAAAAMAAJ&q=isbn:9780881673432&dq=isbn:9780881673432&hl=fr&ei=8E5JTYuLBMO24QaHyeXdCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Les autres neurotransmetteurs, comme la [[sérotonine]] ou la [[noradrénaline]], proviennent de neurones localisés dans des zones particulières du cerveau. D'autres neurotransmetteurs, comme l'[[acétylcholine]] ou la [[dopamine]], proviennent de plusieurs endroits du cerveau, mais ne sont pas distribués de façon aussi ubiquitaire que le glutamate et le GABA. La grande majorité des [[drogue]]s [[psychotrope]]s agissent en altérant les systèmes de neurotransmetteurs qui ne sont pas directement impliqués dans les transmissions glutamatergiques ou GABAergiques<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=J. R.|nom1=Cooper|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=F. E.|nom2=Bloom|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=R. H.|nom3=Roth|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=The biochemical basis of neuropharmacology|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=8|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Oxford University Press|éditeur=Oxford University Press|lieu=|année=2003|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=405|format=|isbn=9780195140088|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=e5I5gOwxVMkC&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Systèmes sensoriels === | ||

| - | {{Voir aussi|Système sensoriel}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | Une fonction importante du cerveau est de traiter l'information reçue par les [[Récepteur sensoriel|récepteurs sensoriels]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 21 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Contrairement aux idées reçues, les [[Sens (physiologie)|sens]] que peut capter le cerveau ne sont pas limitées à cinq. Outre la [[vue]], l'[[ouïe]], le [[toucher]], l'[[odorat]], et le [[goût]], le cerveau peut recevoir d'autres informations sensorielles comme la [[température]], l'[[équilibre]], la [[position]] des membres, ou la [[composition chimique]] du [[sang]]. Toutes ces variables sont détectées par des récepteurs spécialisés qui transmettent les signaux vers le cerveau. Certaines espèces peuvent détecter des sens supplémentaires, comme la vision [[infrarouge]] des [[serpent]]s, ou utiliser les sens « standards » de manière non conventionnelle, comme l'[[écholocation]] du système auditif des [[chauves-souris]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Chaque système sensoriel possède ses propres cellules sensorielles réceptrices. Ces cellules sont des neurones mais, contrairement à la majorité des neurones, ceux-ci ne sont pas contrôlés par les signaux synaptiques d'autres neurones. Au lieu de cela, ces cellules sensorielles possèdent des [[Récepteur membranaire|récepteurs membranaires]] qui sont stimulées par un facteur physique spécifique comme la [[lumière]], la [[température]], ou la [[pression]]. Les signaux de ces cellules sensorielles réceptrices parviennent jusqu'à la [[moelle épinière]] ou le cerveau par les [[nerf]]s afférents. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Pour la plupart des sens, il y a un noyau sensitif principal dans le [[tronc cérébral]], ou un ensemble de noyaux, qui reçoit et réunit les signaux des cellules sensorielles réceptrices. Dans de nombreux cas, des zones secondaires sous-corticales se chargent d'extraire et de trier l'information. Chaque système sensoriel a également une région du [[thalamus]] qui lui est dédié et qui relaie l'information au [[cortex]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Pour chaque système sensoriel, une zone corticale primaire reçoit directement les signaux en provenance du relai thalamique. Habituellement, un groupe spécifique de zones corticales supérieures analyse également le signal sensoriel. Enfin, des zones multimodales du cortex combinent les signaux en provenance de différents systèmes sensoriels. À ce niveau, les signaux qui atteignent ces régions du cerveau sont considérés comme des signaux intégrés plutôt que comme des signaux strictement sensoriels<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 21 et 30 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Toutes ces étapes ont leurs exceptions. Ainsi, pour le toucher, les signaux sensoriels sont principalement reçus au niveau de la moelle épinière, au niveau de neurones qui projettent ensuite l'information au tronc cérébral<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 23 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Pour l'odorat, il n'y a pas de relai dans le thalamus, le signal est transmis directement de la zone primaire, le [[bulbe olfactif]], vers le cortex<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 32 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Systèmes moteurs === | ||

| - | |||

| - | Les systèmes moteurs sont les zones du cerveau responsables directement ou indirectement des mouvements du corps, en agissant sur les [[muscle]]s. À l'exception des muscles contrôlant les [[yeux]], tous les [[Muscle strié|muscles striés]] de l'organisme sont directement innervés par des [[Motoneurone|neurones moteurs]] de la [[moelle épinière]]. Ils sont donc le dernier maillon de la chaîne du système psycho-moteur<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 34 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Les neurones moteurs spinaux sont contrôlés à la fois par des circuits neuronaux propres à la moelle épinière, et par des influx efférents du cerveau. Les circuits spinaux intrinsèques hébergent plusieurs [[réflexe (réaction motrice)|réactions réflexes]], ainsi que certains schémas de mouvements comme les mouvements rythmiques tels que la [[marche]] ou la [[nage]]<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 36-37 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Les connexions efférentes du cerveau permettent quant à elles, des contrôles plus sophistiqués. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Un certain nombre de zones du cerveau sont connectées directement à la moelle épinière<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 33 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Au niveau le plus inférieur se trouve les zones moteurs situées dans le [[bulbe rachidien]] et le [[Pont (système nerveux)|pont]]. Au-dessus se situent les zones du mésencéphale, comme le [[noyau rouge]], qui sont responsables de la coordination des mouvements. À un niveau supérieur se trouve le [[cortex moteur primaire]], une bande de tissu cérébral localisé à la lisière postérieure du lobe frontal. Le cortex moteur primaire transmet ses commandes motrices aux zones moteurs sous-corticales, mais également directement à la moelle épinière par le biais du [[faisceau pyramidal]]. Les influx nerveux de ce faisceau cortico-spinal transmettent les mouvements fins volontaires. D'autres zones moteurs du cerveau ne sont pas directement reliées à la moelle épinière, mais agissent sur les zones moteurs primaires corticales ou sous-corticales. Quelques une de ces zones secondaires les plus importantes sont le [[cortex prémoteur]], impliqués dans la coordination des mouvements de différentes parties du corps, les [[ganglions de la base]], dont la fonction principale semble être la sélection de l'action, et le [[cervelet]], qui module et optimise les informations pour rendre les mouvements plus précis. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le cerveau et la moelle épinière contiennent également un réseau neuronal qui contrôle le [[système nerveux autonome]], la partie du système nerveux responsable des fonctions automatiques. Non soumis au contrôle volontaire, le système nerveux autonome contrôle notamment la [[Hormone|régulation hormonale]] et l'activité des [[muscle lisse|muscles lisses]] et du [[muscle cardiaque]]. Le système nerveux autonome agit à différents niveaux comme le [[rythme cardiaque]], la [[digestion]], la [[respiration]], la [[salivation]], la [[miction]], la [[sueur]] ou l'[[excitation sexuelle]]. | ||

| - | |||

| - | === Systèmes d'éveil === | ||

| - | |||

| - | Un des aspects les plus visibles du comportement animal est le cycle journalier veille-sommeil-rêve. L'éveil et l'attention sont aussi modulés à une échelle de temps plus fine, par un réseau de zones cérébrales<ref name="neural45">{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 45 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Un composant clé du système d'éveil est le [[noyau suprachiasmatique]], petite région de l'[[hypothalamus]] localisée directement au-dessus du point de croisement des [[nerf optique|nerfs optiques]]<ref>{{article|langue=en|prénom1=M. C.|nom1=Antle|lien auteur1=|prénom2=R.|nom2=Silver|lien auteur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traduction=|titre=Orchestrating time: arrangements of the brain circadian clock|sous-titre=|périodique=Trends Neurosci.|lien périodique=Trends in Neurosciences|éditeur=|lieu=|série=|volume=28|titre volume=|numéro=3|titre numéro=|jour=|mois=mars|année=2005|pages=145-151|issn=0166-2236|issn2=|issn3=|isbn=|résumé=|format=|url texte=http://www.columbia.edu/cu/psychology/silver/publications2/149%20antle%20et%20al.pdf|pmid=15749168 |doi=10.1016/j.tins.2005.01.003| consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=}}</ref>. Le noyau suprachiasmatique renferme l'[[Horloge circadienne|horloge biologique]] centrale de l'organisme. Les neurones de ce noyau montrent un niveau d'activité qui augmente ou diminue sur une période d'environ 24 heures, le [[rythme circadien]] : cette activité fluctuante est dirigée par des changements rythmiques exprimés par un groupe de gènes horlogers. Le noyau suprachiasmatique reçoit généralement des signaux en provenance des nerfs optiques qui permettent de calibrer l'horloge biologique à partir des cycles jour-nuit. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le noyau suprachiasmatique se projette dans un ensembles de zones cérébrales, situées au niveau de l'[[hypothalamus]], du [[tronc cérébral]], et du [[mésencéphale]], qui sont impliqués dans la mise en œuvre des cycles jour-nuit. Un composant important du système est la [[formation réticulée]], un groupe d'amas neuronaux s'étendant dans le tronc cérébral<ref name="neural45"/>. Les neurones réticulés envoient des signaux vers le [[thalamus]], qui répond en envoyant des signaux à différentes régions du [[cortex]] qui régule le niveau d'activité. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le [[sommeil]] implique de profondes modifications dans l'activité cérébrale<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Kandel | 2000 | loc=ch. 47 | id=Kandel}}</ref>. Le cerveau ne s'éteint pas pendant le sommeil, l'activité cérébrale se poursuit mais est modifiée. En fait, il existe deux types de sommeil : le [[sommeil paradoxal]] (avec [[rêve]]s) et le sommeil non paradoxal (généralement sans rêves). Ces deux sommeils se répètent selon un schéma légèrement différent à chaque sommeil. Trois grands types de schéma d'activité cérébrale peuvent être distingués : sommeil paradoxal, sommeil léger, et sommeil profond. Pendant le sommeil profond, l'activité du cortex prend la forme de larges ondes synchronisées tandis que ces ondes sont désynchronisées pendant l'état de rêve. Les niveaux de [[noradrénaline]] et de [[sérotonine]] tombent au cours du sommeil profond, et approchent du niveau zéro pendant le sommeil paradoxal, tandis que les niveaux d'[[acétylcholine]] présentent un schéma inverse. | ||

| - | |||

| - | == Le cerveau et l'esprit == | ||

| - | {{Voir aussi|Philosophie de l'esprit}} | ||

| - | |||

| - | La compréhension de la relation entre le cerveau et l'[[esprit]] est un problème aussi bien [[scientifique]] que [[philosophique]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=P. S|nom1=Churchland|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Neurophilosophy|sous-titre=Toward a unified science of the mind-brain|titre original=|numéro d'édition=5|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=|éditeur=MIT Press|lieu=|année=1990|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=546|format=|isbn=9780262530859|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=http://books.google.com/books?id=hAeFMFW3rDUC&hl=fr|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=Churchland|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. La relation forte entre la matière cérébrale physique et l'esprit est aisément mise en évidence par l'impact que les altérations physiques du cerveau ont sur l'esprit, comme le [[traumatisme crânien]] ou l'usage de [[psychotrope]]<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=C.|nom1=Boake|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=L.|nom2=Dillar|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Oxford University Press|éditeur=Oxford University Press|lieu=|année=2005|mois=juin|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=385|format=|isbn=9780195173550|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=1|titre chapitre=History of Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury|passage=|présentation en ligne=|lire en ligne=|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Le [[problème corps-esprit]] est l'un des débat centraux de l'[[histoire de la philosophie]] et consiste à considérer la manière dont le cerveau et l'esprit sont reliés<ref>{{Modèle:Référence Harvard sans parenthèses | Churchland| 1990| loc=ch. 7|id=Churchland}}</ref>. Trois grands courants de pensée existent concernant cette question : [[Dualisme (philosophie de l'esprit)|dualisme]], [[matérialisme]], et [[idéalisme]]. Le dualisme postule que l'esprit existe indépendamment du cerveau ; le matérialisme postule, quant à lui, que le phénomène mental est identique au phénomène neuronal ; et l'idéalisme postule que seul le phénomène mental existe<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=W. D.|nom1=Hart|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=S.|nom2=Guttenplan|lien auteur2=|directeur2=oui|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=A companion to the philosophy of mind|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=John Wiley & Sons|éditeur=Wiley-Blackwell|lieu=|année=1996|mois=|jour=|année première édition=|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=656|format=|isbn=9780631199960|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=Dualism|passage=265-267|présentation en ligne=|lire en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=GFtVBGAn5-YC&lpg=PP1&dq=9780631199960&pg=PA265#v=onepage&q&f=false|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>{{,}}<ref>{{ouvrage|langue=en|prénom1=A. R.|nom1=Lacey|lien auteur1=|directeur1=|prénom2=|nom2=|lien auteur2=|directeur2=|prénom3=|nom3=|lien auteur3=|traducteur=|illustrateur=|préface=|titre=A dictionary of philosophy|sous-titre=|titre original=|numéro d'édition=3|collection=|série=|numéro dans collection=|lien éditeur=Routledge|éditeur=Routledge|lieu=|année=1996|mois=|jour=|année première édition=1976|réimpression=|tome=|volume=|titre volume=|pages totales=386|format=|isbn=9780415133326|isbn2=|isbn3=|issn=|issn2=|issn3=|oclc=|bnf=|partie=|numéro chapitre=|titre chapitre=|passage=|présentation en ligne=|lire en ligne=http://books.google.fr/books?id=kJaCVLZrBcoC&lpg=PP1&ots=Bfyl2mly-x&dq=%22A%20Dictionary%20of%20Philosophy%22%20lacey&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false|consulté le=|commentaire=|extrait=|id=|référence=|référence simplifié=}}</ref>. | ||

| - | |||

| - | Outre ces questions philosophiques, la relation entre l'esprit et le cerveau soulève un grand nombre de questions scientifiques, comme la relation entre l'activité mentale et l'activité cérébrale, le mécanisme d'action des drogues sur la [[cognition]], ou encore la corrélation entre neurones et [[conscience]]. | ||

| - | |||